I read the recently released government documents on strategic foreign policy assessment, national security strategy, defence policy and strategy statement, future force design principles and the security threat environment – three times.

The first time was the ‘soft focus’ speed read that gets you through academic journals and departmental policy documents in reasonable time. Then I waited to see what others had to say before reading everything again – except the security threat assessment which was not then released. That resulted in me publishing National Security Documents Have Little Effect.

After the publication of the security threat environment document, it was time for the “committee stage” (part by part – my third reading). Semantic analysis is one of the major tools I employ in understanding behaviour. However, a detailed breakdown of the internal linkages and gaps in these documents is not the intent of this article.

It is the ‘WHY?’

Why this and why now?

There are plenty of perfectly reasonable explanations:

a. The Royal Commission into the Christchurch mosque shootings made recommendations relating to many issues addressed in these documents and the report had been with Parliament for nearly three years.

b. A large body of policy work came to a natural conclusion and an open, honest and transparent government released them to the public as soon as possible.

c. Parliament is about to dissolve for the election and Cabinet wanted to ensure that, should there be a change of government, this important work would be in the public arena and should continue.

There are also plenty of cynical takes:

d. The government wanted to appear tough on defence and national security in the lead-up to the election.

e. The government realises it is probably out of office soon and left a ‘landmine’ i.e., a massive ‘to do’ list and an equally massive debt for the incoming government to try and reconcile.

f. The Minister, Andrew Little, wanted to leave a personal legacy.

g. Positioning New Zealand favourably, in security terms, in the eyes of other countries leading into ASEAN (4-7 September) in Indonesia, the G20 (9-10 September although not an invitee) in India and APEC (12-18 November) in USA.

h. Shaping public opinion in advance of more far-reaching changes to security, intelligence and surveillance legislation and spending.

It is the last point that I intend to focus on.

The average Kiwi voter does not deep dive into policy. They still get most of their news from TV and other MSM. So, in order to have any chance of shaping public opinion, government must get MSM to report their messages in compelling tones. This triggers secondary commentators such as academics, industry figures, opinion piece writers and finally the social media threads appear.

What messages are crafted into this national security pentalogy?

First – the situation. This comes from the MFAT Strategic Foreign Policy Assessment. To quote from the foreword:

The Assessment makes the case that the present (let alone the future) does not and will not look like the recent past. It points to a global outlook of increased complexity, heightened strategic tension and growing levels of disruption and risk. It sees the impacts of climate change and environmental degradation as significant and undeniable, and technological development as moving at a rapid pace.

The document notes three shifts – from rules to power, from economics to security and from efficiency to resilience.

Message 1 – Your world is getting scarier but we do not yet know what to do about it.

Second – the mission. Refer to the National Security Strategy:

In recent years, New Zealand communities have seen and felt the impacts of national security events first hand. Horrific terrorist attacks, growing disinformation, and cyber-attacks on critical national infrastructure have all left indelible marks. Other harms, such as foreign interference, may be less visible but are no less harmful to our security. These challenges demonstrate that threats to our security can have international or domestic origins and, increasingly, these two elements are intertwined.

Message 2 – The enemy is amongst us and we know from our public consultation and the ongoing ‘conversation’ we are planning that you want us to do something about it.

Third – Execution. Refer to the Defence Policy and Strategy Statement:

· Understand – Defence will have increased awareness of our strategic and operating environments by maximising the use of defence capabilities and technologies;

· Partner – Defence will improve and enhance our partnerships within and beyond New Zealand to support collective security approaches to shared challenges, and maximise interoperability with security partners; and

· Act – Defence will be more ready and able to promote and protect New Zealand’s interests by shaping our security environment and maintaining a credible, combat-capable, deployable force able to operate across the spectrum of operations (from humanitarian assistance through to combat).

READ MORE

- Govt yet to set up national security agency 18 months after Royal Commission recommendation

- SIS identifies several spies in NZ

- The lessons of New Zealand’s China diplomacy

- National Security Strategy Documents Have Little Effect.

Message 3 – We need to spend a lot more money on defence and the NZDF is going to have to be a lot bigger than it is now.

Fourth – Administration, Logistics, Command: There may be a National Intelligence and Security Agency in the future. The Future Force Design Principles “Sliding principles” will be used to ‘set the spend’ by Treasury.

Message 4 – Whoever is the next government will tell you how much this will all cost once the Defence Capability Plan is done next year.

Fifth – ‘Build the fear’ Intelligence Update. The NZSIS unclassified security threat assessment lists violent extremism, foreign interference and espionage as threats.

There are a small number of states who conduct foreign interference in New Zealand but their ability to cause harm is significant.

This report highlights the activities of three states in particular: the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Islamic Republic of Iran and Russia.

Message 5 – We need a lot more intelligence and surveillance powers to keep you safe.

Hybrid Interference

There is a recurring theme in these documents about growing domestic risk before we even get to the discussion about being able to project and sustain meaningful lethal force in our region. This is where the discussion of foreign or hybrid interference comes in. I intend to use the term ‘hybrid’ as not all these threats originate from foreign sources.

I refer to hybrid interference as ‘bridgehead activities.’ By this I mean that they are designed to place the hostile actor in a position from where they can reinforce and exploit. The attacks can involve any combination of:

a. Espionage

b. Terrorism/Violence

c. Insider Threat

d. Subversion

e. Organised Crime

f. Sabotage

They are designed, in the first instance to degrade morale, trust, loyalty and belief in our cause.

However, the targets of these attacks have become disenfranchised due to a much wider range of circumstances than the SIS report discusses. In their report, the factors shaping our security and intelligence include increased strategic competition, declining social trust, technological innovation and global economic instability. The report’s executive summary states:

The challenge for security agencies like NZSIS is to find ways to manage these threats while also upholding the values of a democratic society, such as human rights and privacy – considerations that will not be made by those who do not share the same principles.

The last sentence in that quote sounds to me like the plaintiff wail of “It’s not fair that we have to fight fair.”

It is because of the perception of state over-reach in many facets of life that social trust is in decline.

This leads to the decision to name China, Russia and Iran as malicious actors. This is not new and neither is it fake news. It is a fact that anyone who keeps track of current events is aware of. But how many Kiwis have heard of Professor Anne-Marie Brady? How many know that Russia has served mobilisation notices on its citizens who live in NZ to go fight in its illegal war in Ukraine. Surely people have noticed Iran’s latest party trick of hijacking tankers?

But why stop there? Why not publish a full list? And why pretend that our partners and friends don’t also seek to influence our society and politics? To use the SIS report case study method for a notional example:

During the period between the declaration of results and a coalition government forming in a New Zealand general election, a likely undeclared foreign intelligence officer from a friendly partner-state contacted a member of one of the negotiating parties to the coalition. This contact was completely random with only the most tenuous reasons of a ‘blast from the past’ – limited connection from over twenty years before. The New Zealander agreed to a meeting in a public café where the likely foreign intelligence officer rather clumsily tried to reveal that he had information about the other which might be embarrassing. The New Zealander immediately identified this as a potential attempt to interfere in the formation of the government and offered the likely foreign agent the opportunity to meet again in three days, after which the coalition would be decided and in a place where they could arrange surveillance. The likely foreign agent never made contact again.

Leading authority on the subject, Mikael Wigell, describes hybrid interference methods well, “The key Western democratic cornerstones – state restraint, pluralism, free media, and open economy – provide loopholes for covert interference that can be exploited through the tactical combination of clandestine diplomacy, geoeconomics and disinformation. Indeed, as a strategic practice, hybrid interference is deliberately tailored to exploit the ‘open platform’ inherent in Western democracy.”

In order to counter these attack vectors, do we wish to have a less restrained state, homogeneous society, controlled media and command economy? Of course not. That is why we must be continually alert to any attempts – including those under the guise of ‘keeping us safe’ – that essentially reduce our freedoms and constrain the most important features of our liberal democracy.

Hybrid interference involves the use of non-military approaches to desired outcomes. Most of the techniques employed by security agencies are derived from military techniques. This has not and will not work. The well-intentioned proposals of ‘hate speech’ laws, online ‘regulator’ (censor), disinformation projects, attempts to coerce social media enterprises and so on have not worked and will not work. Neither does the traditional bastion of academic freedom, the universities, picking and choosing who can speak on their campuses. The answer is more free speech not more of the coercive power of the state.

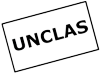

Wigell suggests a whole new toolbox of democratic countermeasures which he labels ‘Democratic Deterrence.” This is a whole-of-society approach with government acting only in a coordinating role where containment is the outcome sought not elimination. It is compared with traditional approaches in this diagram.

Looping back to the pentalogy of security documents there is nothing, on the surface, that is wrong with them. However, there is much missing. Surely, the experience of covid-19 restrictions and the occupation of parliament grounds was a source of learning? Greater restrictions, a more coercive state and crackdowns on everything that gets politicians a soundbite will not make our society more resilient to the hybrid interference pressures we face. A greatly increased security, intelligence and surveillance capability will not either. It is clearly a case of the proposed cure being worse than the disease. We can do better.