It wasn’t that long ago that Australian and New Zealand prime ministers were falling over themselves to run trade missions to the People’s Republic of China. Both governments lobbied hard for and secured early free-trade agreements, and both strongly promoted goods and services trade and all manner of bilateral agreements with the PRC.

It was an age of activity that viewed today looks frenzied.

Those efforts helped tether the trans-Tasman economy to the PRC. The resulting dependency has come under intense scrutiny as human rights, geopolitical, geoeconomic and diplomatic challenges have grown, and as the Chinese economy has slowed.

Australasian relations with the PRC have evolved in response. The heart of the recalibration is a rebalancing of the risk–opportunity calculus and a more careful consideration of each country’s national interest.

This shift has occurred quietly in New Zealand, largely due to the absence of the dramatic events that characterised Australia–China relations and a keen recognition of New Zealand’s trade dependency, but nonetheless that evolution is strikingly similar to the Australian experience.

This shouldn’t surprise anyone familiar with trans-Tasman relations.

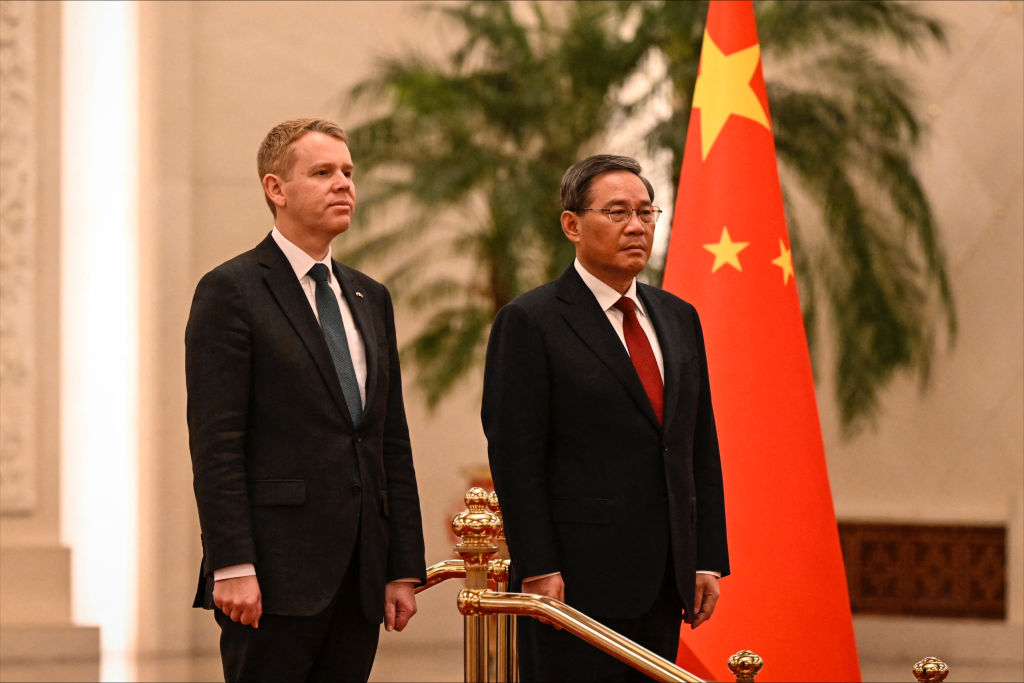

At first glance, Prime Minister Chris Hipkins’s state visit to the PRC in June—in the company of 29 business representatives—appears to fit the earlier Australasian model of engagement with China. It focused on economic engagement, assuaged concerns over a growing list of challenges and differences in the relationship, and deliberately provided the Chinese government with a public relations win at home and abroad.

This was the first PM-led business delegation to China since April 2016, and the first PM visit since April 2019. It followed a ‘robust’ meeting in Beijing in May between Foreign Minister Nanaia Mahuta and her Chinese counterpart Qin Gang during which concerns about the human rights situation in Xinjiang, the erosion of rights and freedoms in Hong Kong, developments in the South China Sea, increasing tensions in the Taiwan Strait and the importance of engaging through regional institutions in the Pacific, especially on security matters, were all raised.

READ MORE

- China's Ambassador says relationship with New Zealand 'going well', won't discuss Beijing's intentions in Pacific

- Government accused of neglecting Pacific partnerships as China's influence grows

- China says New Zealand athletes 'welcome' at Beijing Winter Olympics despite no ministerial representation

- China asks UN to bury highly-anticipated report on human rights violations in Xinjiang

With these positions outlined and differences aired at a high level, the PM’s June visit went ahead with a focus on trade and economic opportunities and on managing the theatrics of PRC diplomacy. If achieving these limited goals was the purpose of the visit, then it was a resounding success, but no doubt tough conversations were also had behind the scenes.

What then of the prospects for Anthony Albanese’s mooted plans for his own China visit later this year? Here are some takeaways from the New Zealand experience.

First, robust discussions about differences are part and parcel of diplomacy with the PRC today, and while they are unlikely to get any easier, they need not prevent high-level diplomacy. Dropping longstanding positions and concerns is not a prerequisite to a high-level visit.

The very week that Hipkins was in Beijing, Immigration Minister Andrew Little released a ministerial communiqué with Australia, Canada, the UK and the US on countering foreign interference, cybersecurity, engagement with the technology industry and national resilience. While country agnostic, these are areas that New Zealand has signalled as concerns in its relations with the PRC and on which it is actively working with partners.

Beijing could have reacted to this, or previous joint statements New Zealand has made, and chosen to derail the visit, but it didn’t. Just as New Zealand has interests to pursue through high-level engagement, so too does Beijing. Faced with a sluggish economic rebound from the dynamic zero-Covid restrictions and troubled relations with the US, the EU, Japan and Korea, Chinese leaders need to demonstrate that they can still promote Chinese interests through diplomacy.

Second, PRC media frame high-level visits as the state sees fit, making it important to get the government messaging right.

In the New Zealand case, PRC media still follow a high-level assertion from 2014 that the New Zealand–China relationship is a model of relations between countries with different social and economic systems. The media use this framing to promote New Zealand business confidence and to critique New Zealand’s closest partners, especially the US and Australia, putting New Zealand in a difficult position.

In contrast, New Zealand’s public message was that China is an important partner and New Zealand is open for business. This glossed over the complexities of the relationship in favour of mercantile interests. The upside of the message was that it received a positive response in Beijing. The downside was that it avoided the challenges in the relationship and sent an unrealistic signal to New Zealand businesses.

Third, any high-level visit to the PRC forces liberal democracies to embrace contradictions and swallow the odd dead rat.

New Zealand is experiencing a prolonged balance-of-payments deficit driven by rising external inflation. The government has clearly signalled diversification and de-risking as priorities, but they will take time. Most products New Zealand exports are subject to protectionism internationally but still attract high returns in China. The government therefore needs to manage relations with China carefully to protect these interests.

Unsurprisingly, then, when asked by the New Zealand media prior to the visit whether Xi Jinping was a dictator, Hipkins chose diplomacy—responding that he was not. The PM could have chosen a better way of answering the question, while remaining diplomatic, but nevertheless, the emphasis on diplomacy was telling.

Fourth, the theatre of an official state visit, especially one framed as a trade mission, is an effective way of stabilising relations. A symbolic high-level meeting ticks many boxes for New Zealand’s Chinese counterparts, but at the same time it doesn’t need to be much more than that.

The new agreements from Hipkins’s visit were mostly continuations of existing areas of cooperation. There were no new trade goals or New Zealand references to Chinese policies like the Global Development Initiative or the Global Security Initiative.

Instead, the visit was about actively managing expectations, pursuing shared interests and seeking to maintain stable relations—all this done under challenging circumstances and while defending long-held positions. That is particularly important this year as New Zealand’s long-awaited first national security strategy and other defence, foreign policy and security assessments are set to be publicly announced.

The issues for Australia are notably more difficult. The relationship is more consequential for the PRC and therefore harder to manage. Australia has already faced sharper actions in the form of detention of Australian citizens, aggressive diplomacy and ongoing punitive economic sanctions. The resolution of those issues could rightly be viewed as a prerequisite to any state visit.

But a state visit should remain a goal. Diplomacy is the art of influencing others. Although challenging to manage publicly, state visits help stabilise relations and build the foundation for the tough conversations required down the track.