The Government’s new defence capability plan is evolutionary rather than revolutionary – but the bleak environment outlined in the document explains why ministers view greater military investment as a necessity rather than a luxury.

Analysis: In a world on edge amid multiple conflicts – and with little confidence in the United States to act as a security guarantor – New Zealand is joining a growing number of nations seeking greater self-reliance when it comes to their own defence.

The Government’s newly released defence capability plan, outlining $9 billion in new spending over four years and setting a framework for further investment to come, is intended to take the NZ Defence Force “out of the intensive care unit” in the words of Defence Minister Judith Collins.

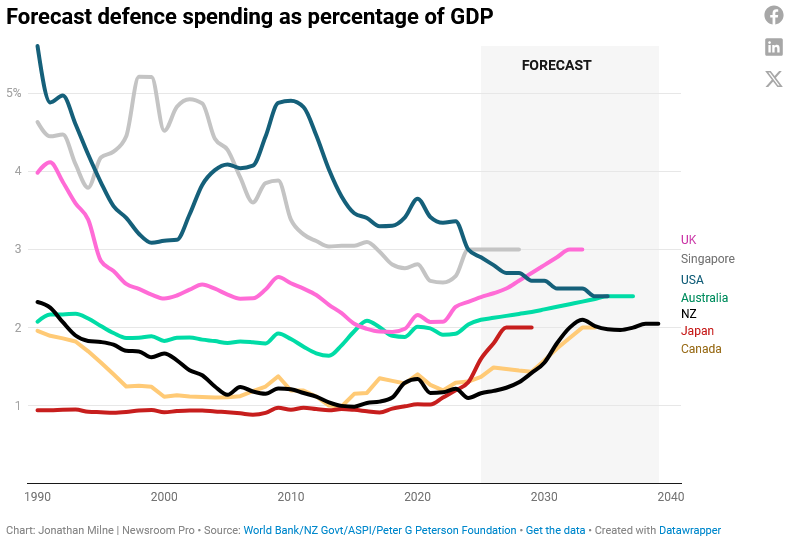

The plan is set to take New Zealand’s military spending as a percentage of GDP from just over one percent to roughly double that within eight years, hitting the two percent target used by Nato nations (although some way short of the new, somewhat arbitrary five percent figure set unofficially by United States President Donald Trump for America’s allies in Europe).

Among the most expensive projects are the replacement of maritime helicopters that operate from Navy ships (estimated to cost more than $2b), new armoured vehicles for the Defence Force (between $600m and $1b), and the replacement of the ageing Boeing 757 fleet (also between $600m and $1b).

Smaller in scale but still significant are plans to invest in uncrewed inflatable boats, drones, and long-range aircraft to support the work of military personnel – something Collins indicated had come about as a result of the extra time taken to finalise the plan.

Dr Peter Greener, a senior fellow at Victoria University of Wellington’s Centre for Strategic Studies and former academic dean at the NZ Defence Force’s Command and Staff College, told Newsroom he and other colleagues had been pushing for greater consideration of such autonomous and remotely-piloted systems for some time, a cause given greater credibility from the experience of the war in Ukraine.

“It’s significant that they were able to inflict the amount of damage on the Russian fleet that they did, including sinking a flagship which was no mean feat, without having a Navy,” Greener said.

He was complimentary of the Government’s broader efforts, saying it appeared to have developed a credible and forward-looking plan that could prove sustainable in the longer term.

“They’re not making promises for spending lots of money immediately, but in looking at the money that will be spent over the next 15 years, it does seem as though they’re intent on coming up with some significant capabilities.”

However, for all that the Government has sought to portray its plan as a major leap forward, the document still (as one would hope) has much in common with its immediate predecessor, produced in 2019 under the Labour-led coalition government.

READ MORE

- Government hikes defence spending amid ‘tectonic shifts’ in geopolitics

- Govt announces huge boost to defence spending

- Government unveils $12 billion Defence Capability Plan

- NZDF drops entry requirements in bid to boost numbers

The replacement of the 757s, maritime helicopters and Southern Ocean patrol vessel were all flagged for replacement within similar timeframes in the 2019 capability plan, while the extension of the Anzac frigates’ lifespan was similarly identified at the time; speaking to media on Monday, Defence Force chief Air Marshal Tony Davies said the ships were still performing valuable work but conceded: “If you go right down to the skeleton of the ship, they are pretty tired now.”

In some respects, the 2019 plan is more comprehensive, setting out indicative costs and a more granular breakdown of the procurement process across a decade, rather than the four years in the 2025 document.

The Government has described that shorter-term focus, and a plan for reviews of the capability plan every two years, as a positive that allows for defence investments to remain more up to date with changing circumstances – a view shared by Centre for Strategic Studies director David Capie.

“It’s good to see the commitment to revisit the plan every two years to make sure the investment matches the rhetoric, and that the plan is still appropriate for the scale of challenges New Zealand is facing,” Capie, a member of a ministerial advisory panel on defence policy, told Newsroom.

But the most striking difference between the 2019 and 2025 capability plans comes in tone.

The last government framed its proposed defence investments as a necessity for community and environmental wellbeing, with a chapter dedicated to the climate crisis.

That was in part a reflection of the coalition dynamics at the time with the defence minister at the time, New Zealand First’s Ron Mark, needing the support of the Greens alongside Labour. But it was also a nod to public squeamishness about the potential role of the military in fighting any conflicts that came its way.

There is no such reticence in the 2025 plan, which includes an emphasis on “enhanced lethality” and investment in enhanced strike capabilities through new missile systems.

Asked by one journalist whether the Government was moving from a humanitarian Defence Force to a more offensively-minded iteration, Prime Minister Christopher Luxon disagreed: “We don’t see it that way. We want to improve the lethality of our Defence Force – no doubt about it. We want to improve the interoperability and the force multiplier, but we can do both.”

Luxon and Collins both indicated they wanted an end to the “stop, go, stop, go”

The plan’s assessment of the current strategic environment also represents a further ramping up of concern about what is described as the “most challenging and dangerous strategic environment for decades”, with strategic interest in the Pacific, the Southern Ocean and Antarctica highlighted.

“China’s assertive pursuit of its strategic objectives is the principal driver for strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific,” the document says, raising particular concern about “the rapid and non-transparent growth of China’s military capability”. A nearly identical point was made by Luxon in his keynote address to the Raisina Dialogue in New Delhi last month, but one crucial difference – he did not single out China as the country behind that alarming military build-up.

The Prime Minister denied the plan was “targeted at any one country”, but it was noteworthy that the real-world examples given by Collins in explaining the deteriorating security environment – “Distance, certainly, is no longer any protection for New Zealand – not when we have an intercontinental ballistic missile launched in the Pacific, not when ships with enormous strike power come into our backyard” – related to Chinese actions.

Now the Government has a plan, the next step will be making it a reality, with a heavy emphasis on interoperability – among the key business case principles is following the Australian approach where viable as part of efforts to develop an ‘Anzac’ force – and opting for cost-effective and durable options over bespoke variants.

Recruitment and retention of Defence Force personnel will also be crucial, something acknowledged by Collins as a factor in limiting exactly how much new equipment was acquired in the next few years.

“A platform isn’t a capability until you’ve got the people to drive it, fly it or sail it,” Greener said, noting with interest the Government’s plans to increase the size of the Defence Force by 2500 people over the next 15 years.

Luxon and Collins both indicated they wanted an end to the “stop, go, stop, go” approach taken to defence spending by successive governments in recent decades.

Whether they succeed may not be known for some time – but they have certainly done their best to make the case for a ‘new normal’ when it comes to our military.

Read the DCP 2025 here.