Phil Plait has mixed feelings about the moon-landing hoax.

Plait — known as "The Bad Astronomer" to his many thousands of readers on Syfy — told Space.com he is frustrated that he and others like him still have to debunk the hoax theory from time to time, 50 years after the first moon landing. Then again, Plait became famous because he's so good at debunking in the first place.

Back in February 2001, Fox Broadcasting ran a documentary titled "Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon?" Plait coincidentally had a pile of research ready from a book he was working on, and a friend sent him an advance copy of the show so that he had time to write up a response.

Plait's essay on his personal blog, which he published shortly after the show aired, quickly generated thousands of views years before Facebook, Twitter and today's social media even existed. Fox's TV show propelled Plait's writing to a large audience, and his 2002 book "Bad Astronomy: Misconceptions and Misuses Revealed, from Astrology to the Moon Landing 'Hoax'" (Wiley) helped as well. Plait remains a popular science commentator nearly two decades later.

"I kind of wish it had never aired," Plait said about the Fox documentary, "because it opened a huge Pandora's box. On the other hand, it's exposing a wound to sunlight. That thing was there anyway, festering. Let it get out to the public, and let it heal, and let it kill the infection. But yeah, it's troubling. Just to know that if Fox hadn't aired that, who knows what my career path would have been."

Bond, Hyams and Mulder

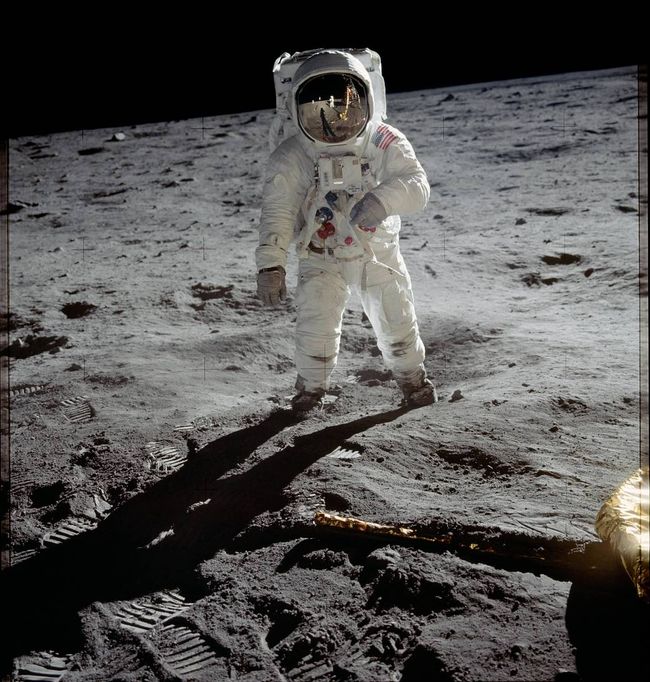

Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepped onto the lunar surface on July 20, 1969. Even back then, some people were skeptical that the feat was technologically possible. The James Bond movie "Diamonds Are Forever," for example, had a joke about faked moon landings just two years later, in 1971.

But what really propelled the conspiracy theory into popular culture, Plait said, was the 1978 Peter Hyams film "Capricorn One," which portrays a faked human landing on Mars. (Also, a 1976 self-published pamphlet by Bill Kaysing, "We Never Went to the Moon," was popular among conspiracy-minded people of the day.)

That was 40 years ago, but moon-hoax enthusiasts are still with us today.

"The X-Files" brought all sorts of space conspiracies into the public consciousness in the 1990s and 2000s, and the rebooted version of the show addressed the moon landing in a 2018 episode. The conspiracy was also addressed in many other fictional TV shows, from "Futurama" to "Friends."

Meanwhile, some documentary films and reality-TV efforts — a 2008 episode of "MythBusters," for example — tried to chase away the conspiracy theory by educating people. Other filmmakers, such as the folks behind the 2002 mockumentary "Dark Side of the Moon," spoofed moon hoaxers.

Opinion polls over the years regularly show that around 5% of Americans believe the Apollo moon landings were faked, former NASA chief historian Roger Launius recently told the Associated Press. That's more than 16 million people, assuming a U.S. population of 327 million.

NASA has done a lot of debunking work over the decades, including a 2018 offer to NBA superstar Stephen Curry to view moon rocks at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston after Curry said he didn't believe in the moon landings. (A few days later, Curry said he made the comments in jest.)

Earlier this year, NASA spokesperson Allard Beutel recited a pile of evidence supporting the moon landings to The Washington Post. He mentioned the returned moon rocks, the ability to bounce laser beams off gear the astronauts left behind and images NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter took of the Apollo landing sites in 2011. Nevertheless, even former astronauts have found themselves in the fray.

Space shuttle astronaut Leland Melvin tackled the topic in the 2019 Science Channel series "Truth Behind the Moon Landing," which also features Space.com Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik as a guest. And in 2002, Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin punched moon-landing denier Bart Sibrel in the jaw during a taped confrontation. (Police later said Aldrin was provoked, and no charges were filed.)

Should we even talk about it?

Plait said there is a danger in talking about the moon-landing conspiracy and other clearly debunked conspiracies like it, such as vaccines causing autism or humans not being responsible for climate change. It's possible, he said, that by airing any of these debates, the media gives legitimacy to the conspiracy. Plait said he sometimes struggles about whether to address a conspiracy in his blog; he tries to discuss ones that are widely talked about already.

But it's a tough job in fast-moving social media. Plait said he recently commented on what appeared to be widespread Twitter backlash about the new version of "The Little Mermaid" starring black actress Halle Bailey, only to discover the backlash was itself likely faked. Plait took down his original tweet and wrote a correction. (The genesis of the viral tweet was from a troll account, according to a tweet by Buzzfeed's Brandon Wall.)

Plait said we should remember that conspiracy beliefs often have real-life effects. For example: "Because of the anti-vax movement, babies are dying, kids are dying, older people are dying, people with compromised immune systems are dying." Extreme weather events driven in part by climate change are killing people as well, he said.

Plait clarified that he did not blame any particular political position for this strife — not even the alt-right, as it doesn't "play into their ideology" (which he said targets people of certain religious groups). But nevertheless, he added, "All of this stuff has been corralling the imagination of the American public and forcing it in a direction to not think critically, and to react instead of sitting and thinking a moment about things, and to doubt — even when you can lay a paper trail from Point A to Point B right in front of someone. They won't believe it."

But Plait still tries. He remembers being on a radio show not too long ago, going over the usual arguments conspiracy theorists use — for example, why are there no stars in the sky in Apollo pictures of the lunar surface? (The reason is the cameras had fast exposure times and the stars were too faint to show.)

"Then somebody called in with some bizarre, trivial thing that made no sense at all," Plait recalled, "and bless him, the radio host jumped in and said, 'Listen. This guy said your 10 biggest claims are wrong. At what point do you back down?'