Scientists have labelled the Government’s plan to swap the Covid-19 alert levels for a “traffic light” system once all regions have achieved 90 per cent full vaccination for their eligible populations as “unethical”, with some fearing it may leave Māori and Pacific people vulnerable to the virus.

The shift in how Aotearoa will manage the virus flew in the face of Health Minister Andrew Little's commitment that restrictions would remain in place until all groups had hit the 90 per cent coverage milestone, said Dr Rhys Jones, a public health physician and senior lecturer in Māori health at the University of Auckland.

“It is extremely disappointing that the threshold used to determine easing of restrictions is based on total population vaccine coverage and doesn’t include a requirement for a certain level of coverage among Māori and Pacific communities,” he said.

“I believe it is unethical to significantly ease restrictions any further while vaccine coverage for Māori and Pacific remains dangerously low. Māori and Pacific populations are at much higher risk of serious outcomes from Covid-19 than other ethnic groups, so it is essential that we get vaccine rates up as high as possible.”

Several other experts raised similar concerns.

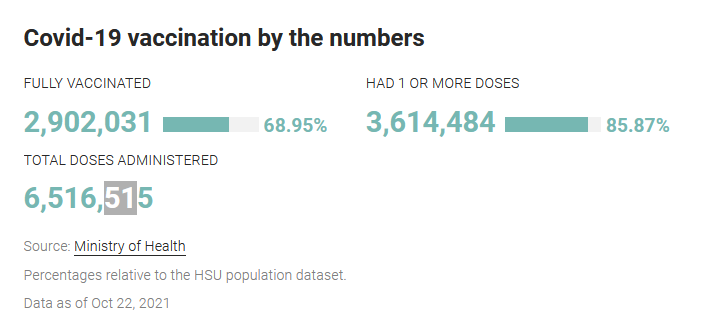

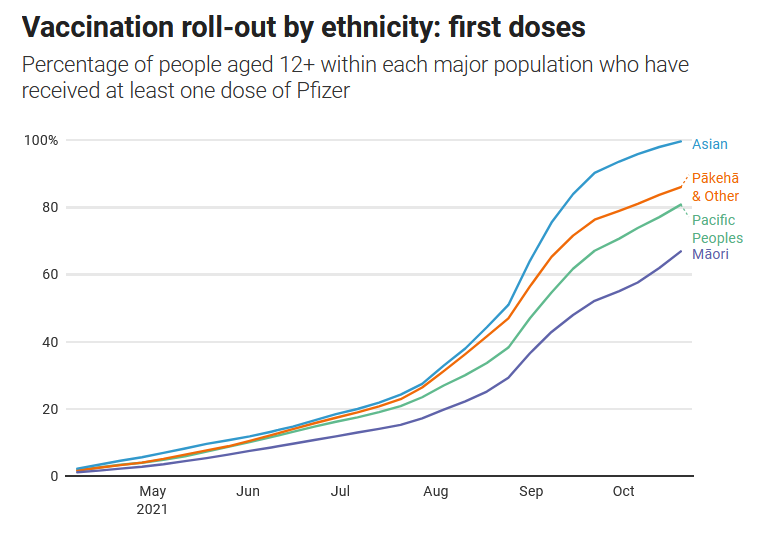

The fears come as the latest figures from the Ministry of Health showed 86 per cent of New Zealanders aged 12 or older have had at least one dose of the Pfizer vaccine, while 69 per cent were fully vaccinated.

However, coverage is much lower for Māori, at 68 per cent for first doses and 47 per cent for second shots. Pacific people also have lower rates: at 82 per cent and 62 per cent respectively for the eligible population.

The Government could begin the traffic light system for Auckland even sooner than the rest of the country if all three of its DHBs’ eligible populations get to 90 per cent double-dosed.

Immunologist Dr Dianne Sika-Paotonu said “at the very least” New Zealand needed to achieve 90 to 95 per cent immunisation coverage for Māori and Pacific people.

“Leaving any of our most vulnerable behind and unprotected, given the adverse health impact already seen for vulnerable groups in Aotearoa New Zealand, will have consequences that will be far-reaching and will speak to generations to come,” said Sika-Paotonu, who is associate dean (Pacific) and head of Otago University's Pacific Office in Wellington.

“Just as we can look back into history and reflect upon mistakes made in the past resulting in irreparable harm for certain groups, others in future may well have the opportunity do the same with our Covid-19 response if we ignore the needs of some of our most vulnerable in society.”

Epidemiologist and senior researcher in public health at Otago University Dr Amanda Kvalsvig said the traffic light system had not been designed to uphold Te Tiriti O Waitangi.

She was also concerned it was short-sighted, leaving children exposed: “The plan may very quickly go out of date”.

Kvalsvig’s colleague, professor Nick Wilson, from Otago University's public health department, said it would have been better for the Government to revise the alert level system – a move for which he, Kvalsvig and other colleagues, such as professor Michael Baker, had been advocating for months.

Wilson was also concerned that the Government was yet to signal a tightening of the borders around the Auckland and Waikato regions, which remain at alert level 3 with active Covid-19 community cases.

Lady Tureiti Moxon, managing director of Te Kōhao Health, who has been leading the roll-out at Hamilton’s Kirikiriroa Marae, was more optimistic.

While she said it would take some time for Waikato to reach 90 per cent fully vaccinated, the region had seen a boost from Super Saturday.

“We did very well, we had lots of families, Māori families vaccinated here on the marae.”

Moxon said the Government’s announcement over the $120 million for Māori vaccination rates was the “biggest effort” in terms of a Māori response.

“Māori providers have said from the get-go that we want to be at the forefront of all this, we want our people to be vaccinated and we want to do it in our way,” he said.

“In the end what we know, from our history from Māori, if we don’t intervene and try and head this off we are going to be worse off than we are now.”

Associate professor Helen Petousis-Harris, a vaccinologist at the University of Auckland, also welcomed the boost in funding for Māori vaccination, saying resourcing was key.

“You can’t just rely on people getting this done, you’ve got to have the staff, this effort takes money.”