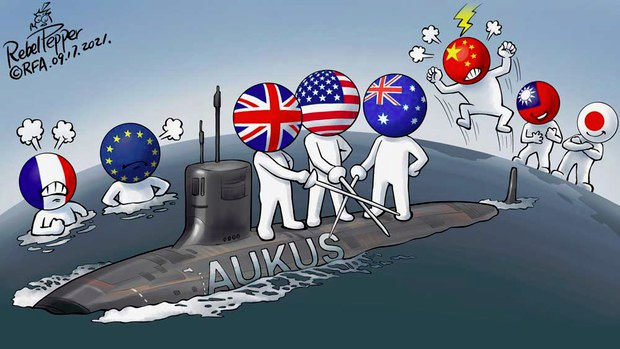

OPINION: New Zealand commentators continue to mull over the significance of Aukus, the Australian-UK-US security arrangement announced on September 15.

Kiwis, naturally, will have a range of responses to it. Whatever they conclude, I believe three fundamental points should inform thinking.

First, Aukus should put to rest scepticism about America’s staying power in the region. Long perennial in discussions of Indo-Pacific security, such doubts intensified under Donald Trump and flared again following Kabul’s chaotic fall last month.

Students of regional strategy largely understand the depths of America’s commitment, but popular views are less clear.

The transfer of nuclear submarine propulsion technology to Canberra under Aukus could not offer a clearer statement of Washington’s intent.

America’s nuclear propulsion programme is one of the crown jewels of its national defence – and with good reason. Nuclear-propelled submarines offer unparalleled range, endurance, and stealthiness. Only six countries deploy them, fewer than those that possess atomic weapons.

A four-star admiral runs America’s programme, and, given its sensitivity, he serves the longest standard term in the US armed forces, eight years. It’s no wonder Washington has shared the technology only once in its history – with London, over 60 years ago, at the height of the Cold War.

Only the president of the United States personally could have made such a momentous choice. Make no mistake about it: a US-Australian submarine propulsion partnership, in and of itself, will anchor America in the region into the final decades of the 21st century.

Second, the three parties’ decision to establish Aukus is a wake-up call for those who have ignored or discounted the significance of China’s military rise.

For Washington, the People’s Liberation Army’s modernisation and aggressive posturing are not a challenge to some cartoonish American aspiration to remain the Indo-Pacific’s top power.

Instead, when the United States looks at the region, it sees growing threats to an order that has delivered peace and prosperity generationally for itself, its friends and allies, and, indeed, for China and the planet as a whole.

It looks at a discrete collection of important – in some cases, vital – US interests that are now under unprecedented pressure due to Beijing’s peacetime military expansion.

The stakes could not be much higher, and, indeed, would have had to be for Washington to decide to share its nuclear submarine propulsion technology, even with so close an ally as Australia.

READ MORE

- Why it's not awkward to be left out of AUKUS

- Russia sees a threat from AUKUS, and a chance to market its own submarines

- Australia’s New Nuclear Submarines Target China

- "The Collapse of New Zealand's Military Ties with the United States"

Third, the most important immediate consequence of Aukus is political, not military. The first Aussie nuclear-propelled submarine is unlikely to make its maiden voyage until well into the 2030s. For now, the trilateral arrangement is most significant as a political statement to Beijing – as Washington, Canberra, and London surely intended.

It occurs as concerns about Beijing deepen across the region. India, Japan, Australia, and the United States on Friday in Washington will convene an in-person summit meeting of the Quad, the co-operative partnership that is yet another response to PRC behaviour. These are four democracies, facing a host of foreign and domestic challenges, that would far rather not be diverting resources to meet a rising military threat.

Meanwhile, Singapore has commented on Aukus in neutral, implicitly positive terms, and other countries have responded to last week’s surprise announcement with equal nuance.

The political, economic, and, yes, security responses by this growing number of Indo-Pacific countries underscore regional discomfort about PRC behaviour. Nobody wants a war in the region, hot or cold, or to be forced to choose between prosperity and peace.

The preferred outcome is clearly for Beijing to decide its own interests are better served by a more benign approach. In practical terms, at any rate, China has years to change course before Aukus acquires military as well as political potency.

For Kiwis, this is a time to take stock. Wellington’s perspective is necessarily different from the one in Washington or Canberra. But the time clearly has come to look at China’s behaviour straight on.

It’s not the United States, Australia, or the UK that has pursued a massive peacetime military build-up in the region. None of them has fabricated islands in the South China Sea. None of them is routinising provocative military operations against Taiwan.

Whatever course New Zealand selects under its independent foreign policy, Aukus is a wake-up call that the region’s strategic environment is shifting in fundamental, inescapable ways.

Ford Hart was an American diplomat for 33 years, serving as consul-general to Hong Kong and Macau, National Security Council China director, and Special Envoy for the Six-Party Talks. He now lives in Wellington.