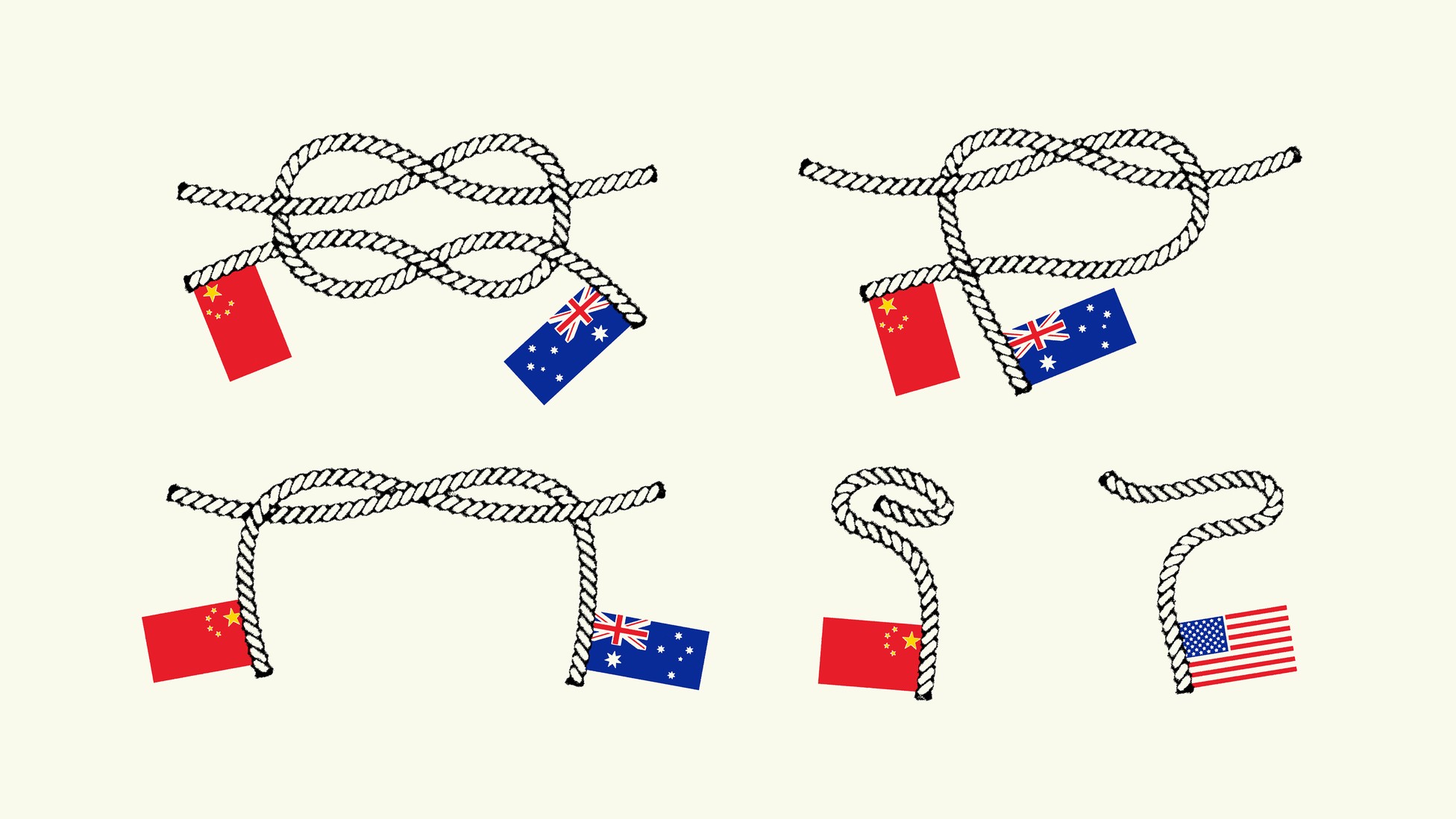

Beijing’s confrontation with Australia should have been an unequal contest. That’s not how it worked out in practice.

“Chewing gum stuck on the sole of China’s shoes.” That’s how Hu Xijin, the editor of the Chinese Communist Party–run Global Times, described Australia last year. The disparaging description is typical of the disdain that China’s diplomats and propagandists have often shown toward governments that challenge Beijing—like Australia’s.

China is now the great power of Asia—or so Beijing believes—but those pesky Australians, mouthing off about human rights and coronavirus investigations, refuse to bend the knee. Beijing has turned to economic pressure to compel Australia to fall in line. “Sometimes you have to find a stone to rub it off,” Hu wrote, of the gum and of Australia. But the Australians have proved impossible to shake, and have instead caused some embarrassment for their image-obsessed tormentor.

The ongoing dispute between Australia and China may seem merely a bilateral affair, fought out in a remote corner of the planet. But it matters around the world.

Australia is a crucial American ally in Asia, so China’s actions toward the country inevitably affect both Washington’s policy and its standing in the region. Australia is representative of many countries: a midsize nation whose economic relationship with Beijing is vital for growth and jobs but, simultaneously, whose politicians and citizens are becoming more concerned about China’s repressive tactics at home and aggression abroad.

The deteriorating relationship between the two countries thus reveals a lot about how China’s leaders can and can’t employ their growing diplomatic and economic power, as well as the options, consequences, and costs for countries, such as Australia, that seek to stand up to Beijing.

Australia “really is a bit of a canary in the coal mine,” Jeffrey Wilson, the research director at the Perth USAsia Centre, a foreign-policy think tank, told me. “You should care about what is happening here, because it’s got lessons for everyone.”

The most important lesson is also the most unexpected. On paper, the outcome of a China-Australia showdown looks like a foregone conclusion. China, a rising power with 1.4 billion people and a $14.7 trillion economy, should trample a country of 26 million with an economy less than one-tenth the size. But in a world wrapped in interdependent supply chains and complex political connections, smaller countries can wield a surprising armory of weapons. The U.S.-led global order, still held together by common interests, long-standing relationships, cold strategic calculation, and deeply felt ideals, isn’t ready to crumble before the march of Chinese authoritarianism either. The story instead offers a more intriguing twist: a China that badly wants to change the world but can’t even change an uppity neighbor.

Chinese leaders “are trying to make an example of us,” Malcolm Turnbull, the former Australian prime minister, told me. “It is completely counterproductive … It is not creating greater compliance or affection.” Quite the opposite, he said: “It is confirming all the criticisms that people make about China.”

READ MORE

- US 'ganging up with its allies', is 'the world's largest source of cyber attacks', Chinese foreign ministry claims

- New Zealand Foreign Affairs Minister Nanaia Mahuta is ruffling feathers as her words are closely watched internationally

- China urges New Zealand to 'make the pie of co-operation bigger', after Nanaia Mahuta's 'storm' comments

- Philippines FM Curses Out China “GET THE $#&! OUT!”

That should lift spirits in Washington. Australia is a key pillar of the network of alliances that upholds American dominance in Asia and the Pacific. If anything, Washington’s ties to Canberra are becoming even more important. Australia and the U.S. are members of the “Quad,” a loose grouping with Japan and India that largely seeks to contain China. What happens to Australia, therefore, has tremendous consequences for U.S. power in the Pacific.

“China can’t bash up on the U.S., but it can bash up on its allies,” Richard McGregor, a former Beijing bureau chief at the Financial Times who’s now a senior fellow at the Sydney-based Lowy Institute, told me. “If China can break Australia, then that’s a step to breaking U.S. power in Asia, and U.S. credibility globally.”

Australia’s importance hasn’t gone unnoticed in the White House. President Joe Biden’s top diplomats have been loud and clear in their support for Australia. His Asia-policy czar, Kurt Campbell, said in March that the administration told Chinese authorities, “The U.S. is not prepared to improve relations in a bilateral and separate context at the same time that a close and dear ally is being subjected to a form of economic coercion.” The U.S., he added, is “not going to leave Australia alone on the field.”

The dispute between Australia and China has been brewing for years. Like the U.S. and other democracies, Australia embraced engagement with China, and the two economies became entwined in a highly profitable symbiotic relationship: Australia’s treasure trove of natural wealth became indispensable to China’s rapidly expanding industrial machine. The countries even entered into a free-trade agreement in 2015.

The ink had barely dried, however, when Canberra began to grow nervous about Chinese President Xi Jinping’s bellicose foreign policy. Turnbull, who as prime minister from 2015 to 2018 was instrumental in forging Australia’s response, wrote in his book A Bigger Picture that China “became more assertive, more confident and more prepared to not just reach out to the world … or to command respect as a responsible international actor … but to demand compliance.”

Australia more openly criticized China’s encroachments on the South China Sea—vital for Australian shipping—where Beijing built military installations on man-made islands to solidify its contested claim to nearly the entire waterway. Turnbull also grew alarmed by the sums of Chinese money sloshing around Australian politics, spent to sway government policy in China’s favor. That led to new legislation designed to curtail foreign influence. Then in 2018, Turnbull’s government banned Chinese telecom giant Huawei from supplying equipment for Australia’s 5G networks, considering it too much of a security risk to essential infrastructure. Relations really fell off a cliff in April 2020, when current Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s government called for an independent investigation into the origins of the coronavirus outbreak—a prickly issue in Beijing, where such demands are perceived as politically motivated efforts to tarnish China.

Beijing duly went ballistic. (Hu’s chewing-gum comment was part of the angry response.) To force Canberra to back down, the Chinese government unsheathed what has become its weapon of choice against recalcitrant nations: economic coercion. Among other measures, Chinese authorities suspended the export licenses of major Australian beef producers; imposed punitive tariffs on barley and wine; and instructed some power plants and steel mills to stop buying Australian coal. In all, Wilson, of the Perth USAsia Centre, figures that Australia lost $7.3 billion in exports over a 12-month period. Some industries have been hit especially hard: The rock-lobster industry, almost totally dependent on Chinese diners, was decimated after Beijing effectively banned the delicacy.

“There was probably relative bipartisan unity before, about building up the relationship with China,”

Canberra wouldn’t budge, though. “We have to simply stand our ground. If you give into bullies, you’ll only be invited to give in more,” Turnbull told me. “There is a lot to be said for nuance and artful diplomacy, but you can’t compromise on your core values and your core interests.”

So far at least, the Australians haven’t had to. Beijing hasn’t been able to inflict sufficient pain to compel Canberra to concede. Wilson notes that the sacrificed exports amount to a mere 0.5 percent of Australia’s national output—not pocket change, but hardly a crisis, either. A few industries have adapted by diversifying their customer bases. Some coal blocked by China was redirected to buyers in India. And there was a limit to how hard Beijing could squeeze: Australian iron ore is the lifeblood of China’s construction industry, and Australian lithium underpins the Chinese electric-vehicle industry.

Beijing’s pressure campaign has succeeded in one important respect, though: souring Australians on China. In a recent Lowy Institute survey, 63 percent of respondents said that they see China more as a security threat than an economic partner to Australia—a 22-percentage-point surge in a year—while a mere 4 percent find their own government more to blame than Beijing for the breakdown in relations.

Girded by such public support, Australia’s usually contentious politicians have forged common cause regarding China, unity perhaps even strengthened by Beijing’s coercive tactics, though critics do take issue with some specifics. “There was probably relative bipartisan unity before, about building up the relationship with China,” McGregor said. Now that the tables have turned, he continued, “it’s sort of a bipartisan view in the other direction.”

None of this has persuaded Beijing to rethink its strategy. From the perspective of China’s leaders, the Australians have trod on too many sensitive toes. In the same way the Australians see changes in Chinese policy behind the collapse in relations, Beijing blames Canberra. Zhao Lijian, a spokesperson for China’s Foreign Ministry, said late last year that the “root cause” of the dispute is “a series of wrong moves” by Australian authorities. Shortly after, the Chinese embassy in Canberra handed out a list of 14 grievances to the local press, which included such actions as unfairly blocking Chinese investments and spearheading a “crusade” against Beijing’s crackdowns in Hong Kong and the far-west province of Xinjiang. (Similarly, but more formally, a top Chinese diplomat gave U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman two lists of complaints Washington had to fix to improve ties during talks in the port city of Tianjin earlier this week.)

How the impasse resolves itself is not at all clear, as both sides continue to slug each other. In April, Australia’s foreign minister canceled two agreements signed by the state government of Victoria as part of Xi’s pet infrastructure-building project, the Belt and Road Initiative, claiming the deals were “adverse to our foreign relations.” Then in May, Chinese officials suspended a bilateral economic dialogue.

Much clearer, however, is what the stalemate tells us about China’s position in the world. Ultimately, Beijing’s attempt to use Australia to warn other countries of the costs of taking on Chinese power has ended up instead highlighting Chinese weakness.

China remains too reliant on the outside world to fully exploit its market leverage, and it still lacks the tools to project its power beyond its own borders in the way that the U.S., for instance, capitalizes on the primacy of the dollar to extend its reach. Rather than scaring other governments into sullen silence, the unsuccessful campaign against Australia could embolden them to stand up to China on issues they consider of core importance.

Australia, however, was able to confront Beijing because of its political unity. That’s a key takeaway from the Australia story. Policy experts spill a lot of ink about the crucial role alliances between countries will play in the coming contest with China. But those international bonds cannot hold firm without corresponding alliances between national political parties and interests within the allied democracies. We can see such a consensus forming in the U.S., another country where a strong position on China is backed by widespread political support.

At the same time, China’s tussle with Australia could have long-term consequences for its economic ties to other countries. Many policy makers are already concerned that economic dependence on China could compromise their national security. The case of Australia could heighten those fears and, as Wilson speculates, lead to “repricing political risk in terms of economic relationships with China.” The Australia situation “will be a story of how governments and businesses around the world have had to reappraise what having an economic relationship with China is like.”

Yet an even darker message emerges from Australia’s example: China may have failed to change Australia, but Australia hasn’t changed China, either. This holds out the terrifying prospect of a new world order marked by almost constant conflict—if not military, then at least economic, diplomatic, and ideological. That is, unless both sides can find another way.

“China has and will continue to behave badly,” Geoff Raby, Australia’s ambassador to Beijing from 2007 to 2011, told me. “China won’t be changing, and we have to find a way of living with a China that is not like us but is big, powerful, and ugly.”