On March 14, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern said New Zealand's strategy in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic would be to "go hard and go early".

Despite claims from her opponents we didn't, new research has found not only that we did, but we went the hardest and earliest of anyone.

"The speed and intensity of the national response to limit the epidemic is unprecedented internationally," a new study published this week in prestigious medical journal The Lancet said.

"It is likely this early, intense response, which also enabled relatively rapid easing while maintaining strict border controls, prevented the burden of disease experienced in other high-income countries with slower lockdown implementation."

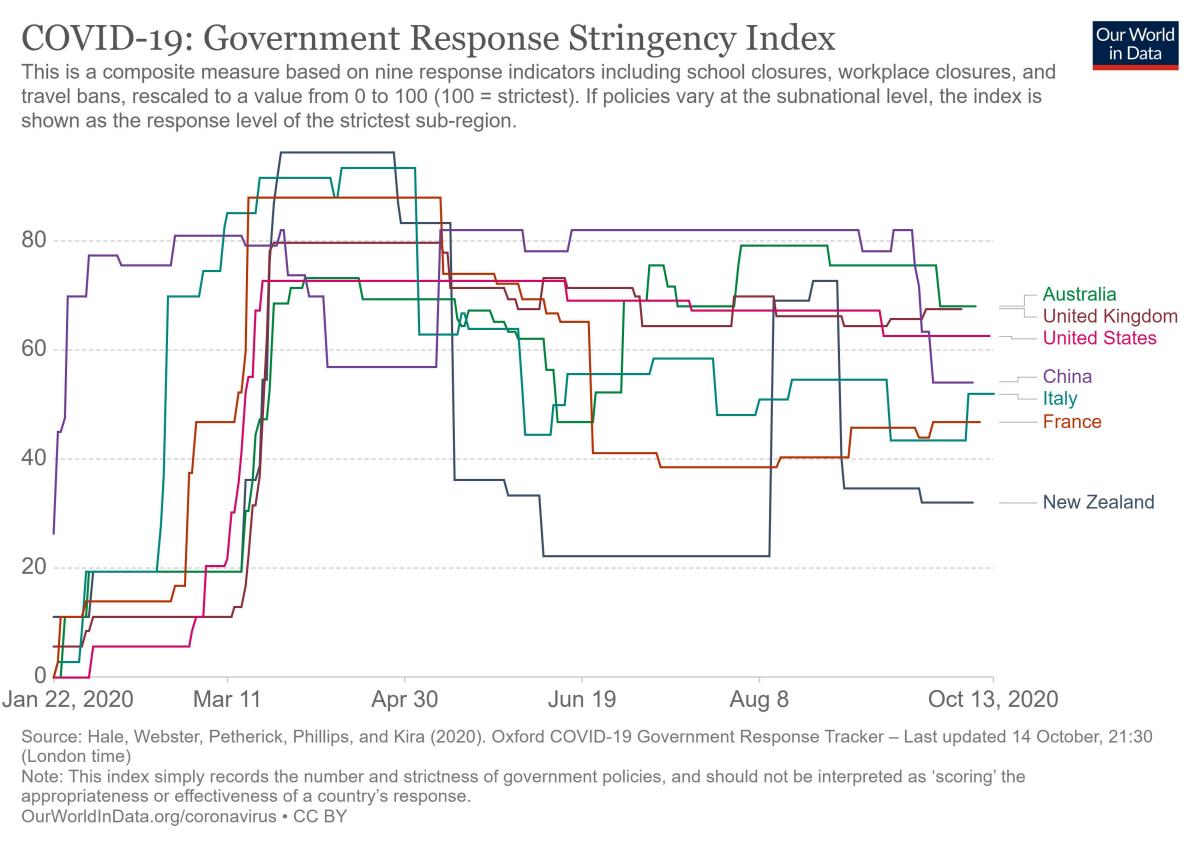

The researchers cited Oxford University's Government Response Stringency Index, which measures how seriously governments around the world have reacted to the coronavirus threat - for example whether schools and workplaces were closed, rules around public events, transport and gatherings, restrictions on movement and travel, and efforts in contact tracing and testing.

Compared to our peers, the index shows New Zealand for a short time had the strongest response in the world - which quickly led to having more freedoms than our friends in the UK, US, Australia, France and Italy, who didn't go as hard and are now paying the price.

- Trump prepares for potential fight; Leaked docs reveal new evidence of China's coverup

- COVID-19 killed triple as many UK residents as pneumonia and flu combined

- New Zealand tops world for response to coronavirus market crisis management

- Donald Trump supporters shocked at COVID-19 diagnosis

Though the chart appears to show New Zealand putting restrictions in later than those nations, that's because our remote location made us one of the last to have cases. We locked down before our first death was recorded - others had dozens or even hundreds before taking action.

"Early and intense implementation of national COVID-19 suppression strategies have effectively altered the course of New Zealand's epidemic and limited the burden of disease and inequities in this high-income democratic setting, initially achieving COVID-19 elimination," the study said.

During that first wave, there were just over 1500 confirmed and probable cases of COVID-19 - most were imported, "with predominant features of healthy travellers: younger adults, European ethnicity, and higher socioeconomic status".

Local transmission - most of which happened before the lockdown - tended to hit "more vulnerable populations", but damage was limited thanks to "rapid suppression of community transmission". The lockdown also bought the health system - which had prepared for an influenza pandemic, not a coronavirus - time to develop testing and tracing capability.

At the start of the pandemic, it took on average almost 10 days for an infected person to be confirmed as having the virus - by the end of the first wave, this was down to just 1.7 days. The time for an infected person to go into isolation dropped from 7 days to negative 2.7 - meaning they were usually already in isolation before testing positive.

The study, led by scientists at the Institute of Environmental Science and Research, said while the strategy worked, questions remain about how cost-effective and sustainable it is, going forward.

"Taiwan has shown that COVID-19 control can be achieved in the absence of complete border closure, although using advanced technological systems and ongoing strict disease suppression strategies in a society that had already normalised some of these measures from previous novel virus exposures."

New Zealand had the advantage though of having "emergency management systems... primed for disaster response", the scientists said, thanks to experience with earthquakes.

Lowered mortality

Separate research published this week in Nature Medicine found New Zealand's response was so effective, fewer people have died this year than would have if there was no coronavirus pandemic - in contrast to countries like the US, where it's likely the death toll from the pandemic has been underestimated. Even Australia, which has struggled to keep its outbreaks under control, has also experienced a lower mortality rate than usual.

"Although sadly, more than 900 people have died from COVID-19 in Australia so far, this is being compensated for by fewer deaths from other causes (including, most notably, seasonal flu)," Griffith University environmental scientist Hamish McCallum said.

- Man escapes Auckland isolation facility by 'creating rope out of bedsheets'

- Two new Covid-19 cases, both in managed isolation

- Canterbury doctor praised by NZ Public Party found to have spread 'misleading' information about COVID-19

- China's capital reports massive explosions; Rumors of bank runs spread; More heavy rain, mudslides

Fewer young men have been dying too, likely due to avoiding injuries.

"At the same time, the authors also concluded that lockdowns undoubtedly have significant negative short- and long-term consequences, including adverse psychological and economic effects," said Alex Polyakov, doctor at the University of Melbourne and Royal Women's Hospital.

"A lockdown strategy should be the mechanism of last resort and can largely be avoided, or significantly shortened, if effective testing, tracing, and isolation measures are in place."

When COVID-19 reemerged in Auckland in August, a full lockdown wasn't enacted - the city going to alert level 3 instead of level 4, and Director-General of Health Ashley Bloomfield saying there had been improvements to the country's contact tracing systems since the first wave.