With astronomers detecting a potential signature of life in the clouds of Venus, there's obviously going to be a big push to get some new space missions to the planet.

We don't know if the phosphine gas recently observed by telescopes is coming from floating microbes or has a simple non-biological origin. Right now, nothing is conclusive. But the only way we're likely to find out for sure is by taking some scientific instruments there.

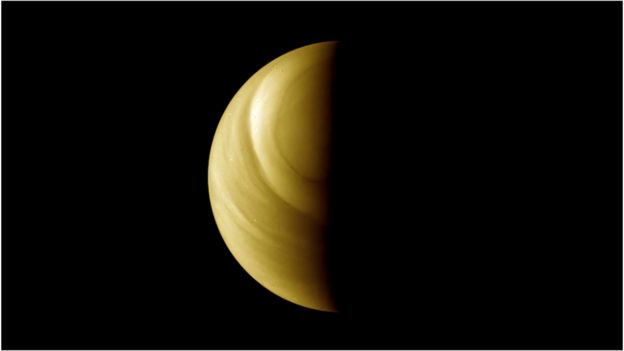

The Japanese space agency's Akatsuki orbiter is the one mission at the planet at present, and it was built long before the phosphine question came up – so it's not really best-suited to study the issue.

What's needed are some dedicated investigations. And the first opportunity we'll probably get to perform these will be with the private Rocket Lab company.

This start-up has been making waves with its small Electron rocket, which launches from the Mahia Peninsula in New Zealand’s North Island.

The company's CEO, Peter Beck, is fascinated by Venus and has already announced his intention to send a mission there in 2023. He's funding and constructing it in-house.

Rocket Lab will do it with the Photon "kick-stage" that goes on the top of an Electron.

In Earth orbit, this stage does the final placement of small satellites in the part of the sky they want to operate. But the Photon is extremely capable and could shepherd a probe to another planet, and even carry some sensors of its own.

- Successfully launched homegrown satellite design could 'triple' Rocket Lab's business

- How small launcher Rocket Lab plans to pull off its first mission to the Moon next year

- Rocket Lab marks new milestone with first-ever NZ built and launched satellite

- Rocket Lab - I Can't Believe It's Not Optical Launch

Beck's plan is to drop off an atmospheric entry probe at Venus. As this falls through the “air”, it would radio back its observations of Venusian clouds to the Photon, which in turn would relay that data back to Earth.

The entrepreneur's team is working on a payload mass of 37kg.

"That might not sound a lot, but 37kg can get you an awful lot of instrumentation, especially if you're now very targeted in what you're looking for and what you're trying to measure,” Beck told BBC News.

"Venus hasn't had a lot of love recently, and I think 2023 is the opportunity to put that right. It's very hard for governments to move quickly but a private mission can. We can go there for a small amount of money, and we can go there many times and have many goes at it, and iterate the learning."

It’s true, the big space agencies operate by a different philosophy. They aim for super, high-fidelity science and engineering – but this means their top-notch missions fly infrequently and at high cost. It's a question of trade-offs.

A Rocket Lab entry probe when it falls through the atmosphere at Venus is not going to spend long in the key zone where phosphine has been detected – between 50km and 60km in altitude. The measurements will be brief.

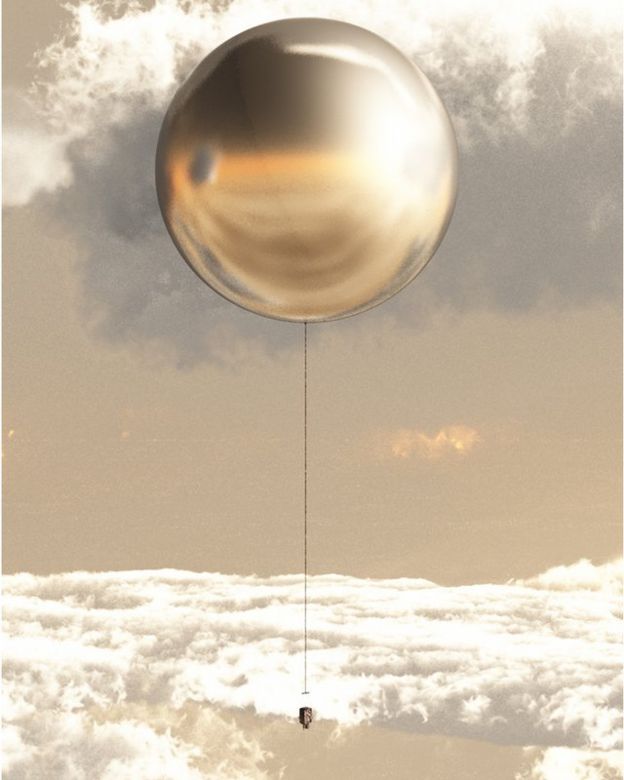

Ideally, what you need is some sort of long-lived platform, dwelling in the clouds of Venus for weeks or months at a time. Like a balloon. That's the kind of thing big space agencies do.

"This would allow detailed measurement of cloud," explains Dr Colin Wilson from Oxford University, UK, who worked on the European Space Agency's Venus Express probe (2006-2014)

"We proposed such a mission – the European Venus Explorer – to Esa in 2010, unsuccessfully. This year, in a Nasa-run Venus Flagship Mission study, we proposed including a balloon that would explore the cloud layer for two months, with specific instruments designed to detect biological material if present."

It's a fantastic idea and follows in the pioneering footsteps of the Soviet Vega balloons at Venus in the 1980s, although they only worked for a couple of days.

The problem is that, even if approved for development, we wouldn't see a Nasa Venus flagship mission - and its balloon - fly until the 2030s at the earliest. And the more modest mission concepts now before Nasa and Esa for consideration are looking at launch slots no sooner than the back end of this decade. Which brings us back to the Rocket Lab type of approach if we want quicker results.

Prof Jane Greaves from Cardiff University led the team that detected phosphine in the atmosphere at Venus. She hopes scientists can find inventive ways of getting new probes to the planet.

“I think in the fairly near-term, we'd like to send even just a really small probe that maybe some other mission could drop off on the way - you know, something going to the Sun. Perhaps it could drop a tiny 'lab on a chip' package through the atmosphere so we can get some new data back."

Peter Beck's message is "give me a call. If anybody wants to join the team, come join us. But, you know, the bus is leaving; we're going!"