Hong Kong police arrested 53 opposition activists and former legislators Wednesday morning, accusing them of "subverting state power." The arrested leaders had been involved in organizing or attending a democratic primary last July, ahead of the fall Legislative Council elections. (Though the full elections were eventually postponed, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 600,000 people voted in the primary.)

The arrests are part of Beijing's attempt to crush dissent in Hong Kong, which had long been semi-autonomous under China's "one country, two systems" policy. When a vague national security law was imposed in June, many Hongkongers feared it would give China cover to undermine the political freedoms they had long enjoyed. Since then, there have been steady, gradual encroachments: Public universities have culled dissident faculty members, police have arrested the pro-democracy media entrepreneur Jimmy Lai, and protesters who attempted to flee by boat to Taiwan have been sentenced to prison. This latest crackdown sends an even bigger message.

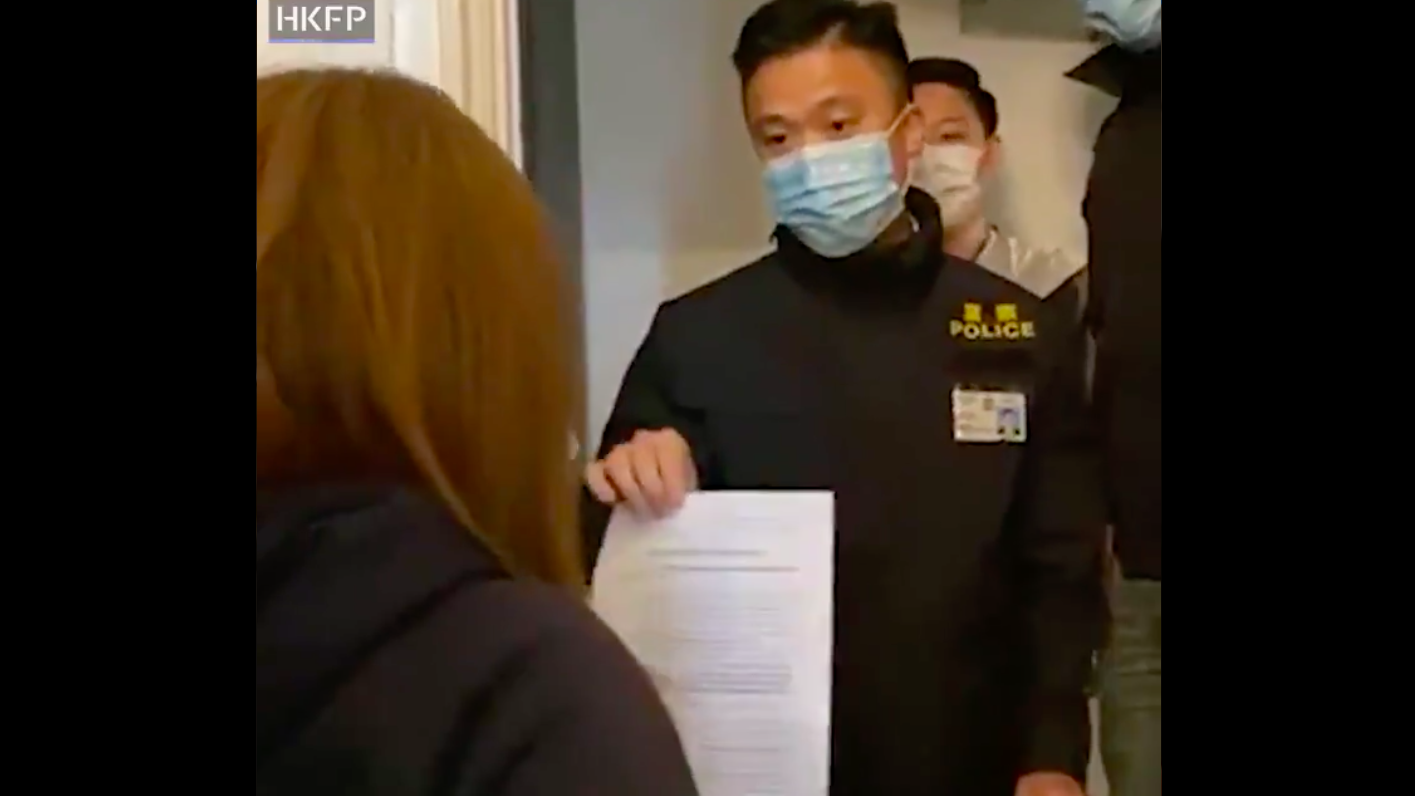

Early this morning, "the police also visited the offices of at least one law firm and three news media organizations to demand documents, broadening the burst of arrests that started before sunrise and sent a chill through Hong Kong's already-demoralized opposition camp," reports The New York Times. The authorities also arrested at least one American, John Clancey, a lawyer who assisted in the primary polls. CNN says that "Clancey could potentially be the first foreign citizen who does not also hold a Hong Kong passport to be arrested under the national security law."

The national security law has been roundly criticized, in the Times' words, "for introducing ambiguously defined crimes such as separatism and collusion that can be used to stifle protest."

Hongkongers have long enjoyed several basic rights—free speech, due process, the right to elect some of their legislators. When Britain handed the city over to China in 1987, a condition of the transfer was that Beijing would allow Hongkongers to maintain these political freedoms and a separately functioning system until 2047, at which point the agreement expires.

Beijing recently opted to seize control prematurely and suppress dissent, moves that have sparked months of protests and led to hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people marching in the streets demanding that their freedoms be preserved.

In the January 2020 issue of Reason, I wrote:

Privately operated newspapers in Hong Kong run scathing critiques of politicians without political reprisal. This does not happen in Shenzhen. While mainland China claims to have freedom of association and expression, it also has vague anti-subversion laws that let the authorities target dissidents….

Hongkongers realize winning full autonomy is unrealistic. But Chinese rule would ruin the freedoms they cherish, and it's unlikely those freedoms would be restored in their lifetimes.

Hong Kong's revolutionaries just want to keep what they have. They're fighting for nothing more, and they will settle for nothing less.

A year later, the city's newspapers no longer run scathing critiques of politicians without fearing political reprisal. But it remains true that full Chinese rule would ruin the freedoms Hongkongers cherish. We're seeing that happen right before our eyes.