Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern says "pace" is her biggest regret from her first two years in office.

Her Government came to power with big plans. And 2019 was to be the year of delivery.

But two years into the Labour-led coalition, what has her Government actually achieved? Stuff takes stock.

Health

Is it possible to win at health? No-one can stop people dying. In fact, the longer people live, the sicker they get, and the more costly their care becomes. At worst, the health portfolio is a hospital pass. That said, it is possible to "win" at health: Helen Clark, Annette King, Jenny Shipley, and Bill English all managed to survive the portfolio and go onto bigger and better things. Will current Health Minister David Clark be able to say the same?

The good news stories come from the Budget. Enormous capital investment – more than $2 billion – has been approved in the last two Budgets to build more hospital and healthcare facilities.

New Zealand is getting some new hospital assets, including a new hospital in Dunedin. Mental health is getting some money too. After a long inquiry, which was subject to some well-deserved criticism, the Government accepted most of the recommendations, which mostly revolved around funding and new services. After years of agitation from the sector, and in broader society, it looks like mental health is being taken seriously by the Government.

But there are some dark spots too: and big ones. National's Michael Woodhouse argues, with validity, that National was on track to spend more than Labour on health this term. The current measles outbreak is also a damning stain on the Government's record in health, its reluctance to crack down on anti-vaxxers. It has led to calls for the reinstatement of more rigorous health targets.

There's also the looming problem of district health board deficits, which rose to $1 billion this year. It's no secret that the DHBs have a massive funding problem. The Government has a friend in Heather Simpson, Helen Clark's former chief of staff, who is reviewing the health system and will make recommendations on fixing it next year. The Government will take these changes to the next election, meaning the 2020 election campaign could focus on how much change – and money – Kiwis want to see in their troubled health system.

Housing

Two years into the Government's term, housing is far from Labour's strong point, but it is not an area of total failure.

The huge shining failure is KiwiBuild, the promise from Labour to build 100,000 affordable homes in 10 years. After months of backdowns and embarrassment over the policy, the Government has significantly scaled it back: getting rid of the 100,000 target, buying back many of the homes to sell on the private market because no-one wanted them, and allowing a small proportion of the homes to sell above the "affordability" cap – which the Government also raised in Auckland.

KiwiBuild is the only policy failure of this Government thus far to lead to a minister losing their job, with Phil Twyford being swapped out of housing and Megan Woods taking over. There are some happy families living in what look to be well-built KiwiBuild developments. But nowhere near enough of them.

The Government has found frustration elsewhere in the housing portfolio. Labour did not persuade NZ First to support a capital gains tax, one of the larger changes it had been keen on to douse down the property investment market. It did manage to extend the "bright line test" and close negative gearing loopholes, although some economists suggest that will drive up rents.

More concretely the Government has passed an effective foreign buyers' ban on residential property, something all three parties agreed on.

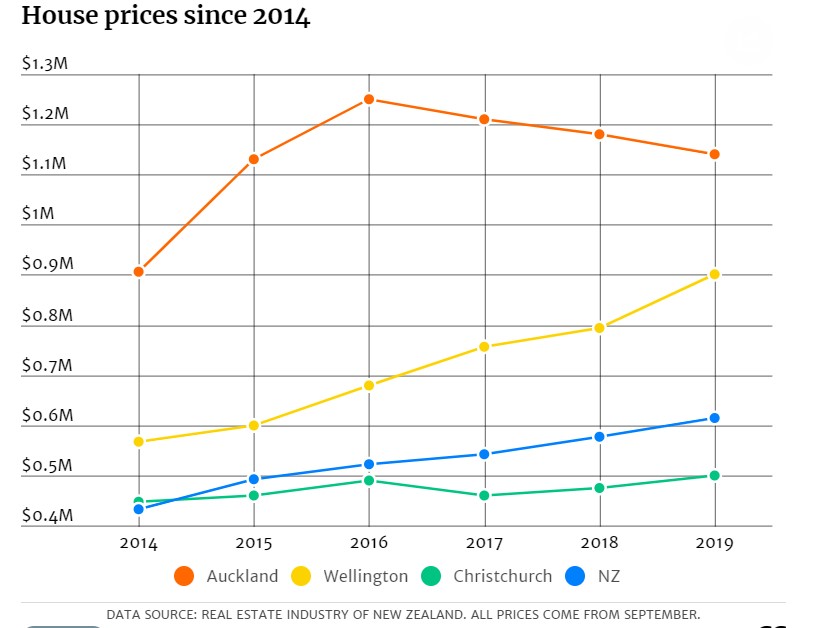

So what effect has this had on the market? According to the Real Estate Institute, median house prices have continued to cool after a peak in 2016, dropping from $1.21m in September of 2017 to $1.14m in September this year. Median house prices in Wellington have grown significantly, however, from $756,000 in that period, and this has helped keep the median price for the entire country on its upwards trajectory, from $541,000 in the month of the election to $615,000 in September of 2019.

In the rental space things have moved very slowly. The largest intervention from the Government has been its Healthy Homes Standards, which set much higher standards for rental properties, but aren't yet in effect. (That insulation change actually comes from a 2016 law.) Labour also promised a much more radical reform of tenancy laws to give tenants more power with an end to no-cause terminations, limits and transparency on rent rises, and the banning of letting fees. In the end, it sliced off the letting fees ban and has pushed all the others out for consultation. A year after that consultation ended we are yet to see an actual bill, although new minister Kris Faafoi promises us something is coming ahead of next year.

Rents have continued a steady rise, particularly in Wellington. The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment's figures for Auckland have average rent rising from $494 a week for new tenancies in September 2017 to $523 in September 2019 – a bump of $29 a week. For comparison, in the previous two years it rose $26 a week.

Finally, Labour promised to do more to support those hit worst by housing costs by stopping state-home sales and rebuilding the state housing stock. It has definitely stopped large-scale state home selloffs and has dramatically increased the overall stock of state homes. There were 61,083 state homes in June 2017 and 61,437 two years later, along with increases in emergency/transitional housing and community group housing too. State house building had been ramping up after National reduced the net stock in its early years in government, giving Labour a bit of a running start. In mid-2019 there were roughly nine times as many public houses being built as there were in 2016.

Child Poverty

The prime minister sought power to lift children out of poverty and two years in is claiming approximate success. Time will tell.

Treasury has estimated the number of children in poverty would reduce to between 10 per cent and 12 per cent due to the Government's package of welfare changes introduced not long after the election. This has Ardern confident that 50,000 and 70,000 children will be lifted from poverty.

The true measure of success will be official poverty statistics, expected to come in 2020.

Poverty is measured three ways, and Labour has put both the measures and a target in law so far this term. The primary measure is children living in homes where income is less than 50 per cent of the median, currently $1016 a week, before housing costs are deducted.

When Labour launched its campaign in 2017, this measure had 16 per cent of children living in poverty.

A second measure shows 23 per cent of children are living in homes where income is less than 50 per cent of the median after housing costs. A third measure has 13 per cent of children living in material poverty, defined through a series of indicators such as lacking two good pairs of shoes, and the ability to see a doctor when needed.

The Government set an official target in May for reducing child poverty, aiming for 70,000 children, or reducing that 16 per cent figure to 10 per cent.

Transport

The Government's transport plans are best described as hastening slowly. Elected on a platform of investing in public transport over highways, progress has been slow.

New Zealand faced an infrastructure deficit, particularly in public transport in Auckland, under the previous government. But the Labour-led Government's management of these new projects – particularly a promised light rail track to Auckland airport – has been found wanting. As detailed in a report by Stuff, the light rail process, led by minister Phil Twyford, has been beset with problems. First the minister fell out with the NZTA board inherited from the previous government, before appointing a whole new board. Then a last-minute bid, allegedly written on six PowerPoint slides, delayed the process by at least a year. At the same time, companies continued to bid for the NZTA rail line plan because they were told it would go ahead. That is now uncertain.

In the meantime, new road construction has been almost completely halted. The good news is a suite of repairs has been carried out on old, unloved, pothole-ridden local roads, but people looking for big new highways will be disappointed. Only the Manawatū Gorge replacement road has been greenlit.

The other side of the Transport portfolio has gone quite well: Twyford led the charge that uncovered that NZTA had neglected its role as transport regulator basically since it was formed in 2008. He orchestrated a massive shake-up which has put safety at the centre of the agency. Hopefully this will eventually reduce a road toll that has climbed shamefully high over the decades.

The Government's electric vehicle policy is also a bright light, promising heavy subsidies for EVs at no cost to the Government. The cost will instead be borne by those who purchase gas guzzlers, who may have something to say about the policy come election year.

Climate Change

Climate Change Minister James Shaw is probably the only person in Ardern's ministry with his actual dream job. But it has been far from a smooth ride. While climate change has dominated the headlines it has not yet dominated the legislative agenda.

The actual enforcement and pricing mechanism for climate change is something the last Labour government brought in – the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). On Thursday Shaw announced the Government would essentially capitulate to farmers' demands that agricultural emissions (about half of our damaging emissions) – would stay out of the ETS until 2025, and possibly forever.

There's a catch, however: the Government is legislating to bring agriculture into the ETS as early as 2022 if the government of the day deems not enough progress has been made towards a new form of pricing emissions, and by default in 2025 if nothing new is worked out.

Shaw's big baby is the Zero Carbon Bill, a complicated framework that would set in law several emissions targets for 2050 and 2030, establish an independent Climate Change Commission to advise governments on how to meet those targets with periodic "emissions budgets", and require governments to respond to them. It sounds a bit vague now but similar policies have worked well in places like the United Kingdom at both depoliticising climate change policy and forcing successive governments to act – much like the Fiscal Responsibility Act has basically forced New Zealand governments to live within their means since the mid-1990s.

The Zero Carbon Bill is well behind schedule, having been held up in negotiations with NZ First and National, which Shaw wants to keep on board to ensure bipartisan support. NZ First already managed to weaken the law somewhat by making sure the Climate Change Commission has no actual power – Shaw himself would have preferred it to be an institution more like the Reserve Bank, which acts independently of government, although it is somewhat doubtful Labour itself would have supported this. Still, the new law does look likely to pass by the end of the year after emerging from a brutal select committee with its key targets intact – with or without the support of National.

Elsewhere the Government banned all new permits for oil and gas exploration, shocking the resources industry. This move went against official advice that said it could cost the economy and might even lift emissions as more fossil fuels might have to be imported. But it gelled with the advice of many scientists, who say we can't afford to burn all the fossil fuels we've already dug up anyway, and should leave others in the ground.

Shaw has also launched a $100m green investment fund, a tenth of the size of the one the Greens campaigned on. This fund has not yet started investing.

And emissions themselves? The data is frustratingly slow to release but all indications are that they continue to grow, and will for several more years at least.

Law & Order

The coalition Government came to office promising to strive towards adding 1800 new police, a commitment to focus on combating organised crime and drugs, to increase Community Law Centre funding, set up a Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCR), and investigate a volunteer rural constabulary programme.

So has it met its law and order targets?

So far it has been a mixed bag and, when it comes to police numbers, it depends on whose interpretation you believe.

Until recently, it looked like it would not meet this key objective for 1800 police but now it seems the goalposts have been shifted, with the Government now saying the figure was in relation to newly trained recruits and not a net gain, which Police Minister Stuart Nash has been promising police. The recruit "goal" now looks set to be ticked off after a police graduation in November.

A focus on combating organised crime and drugs appeared to be trudging along but then gangs and meth emerged as big issues and catapulted the Government into taking more action. The police minister is now bringing proposals to Cabinet for a new law to give police powers to tackle organised crime and deal with gang kingpins, who have heightened the meth problem in New Zealand.

The Government also committed 700 of the 1800 new police to work in serious and organised crime. According to police figures, 143 FTEs have gone into these roles. However, it can take a couple of years for new recruits to go through the training process, so these figures are likely to continue to increase.

It has achieved its promise to increase Community Law Centre funding, which saw a 20 per cent boost last year. This year the Government locked that increase in permanently and, in Budget 2019, locked in further funding of $8.72 million over the next Budget period, bringing the total annual funding to Community Law Centres to $13.26m.

The volunteer rural constabulary programme has been scrapped after being seen as risky and "policing on the cheap". Labour was obliged to investigate the idea as part of their coalition deal with NZ First.

Corrections

The Government aimed to reduce the prison population by 30 per cent over 15 years, improve outcomes for Māori, improve rehabilitation, and reintegration and ensure Corrections has facilities.

In Opposition, Corrections Minister Kelvin Davis was a strong advocate for an overhaul of the lock-them-up approach, instead focusing on reducing reoffending. The Coalition Government has aimed to bring a more humane/wellbeing approach to the Corrections system and targeted blockages in the justice system – trying to reduce the likelihood of future offending by giving extra support to defendants on bail.

It has also strengthened legislation to improve prison security and ensure the fair, safe, and humane treatment of people in prison. It has also set aside more money for housing and support as well as mental health services

Prison Muster

Demographics are locked in decades in advance, so the Government's ambitious goal of significantly reducing the prison population will take years to bear fruit.

The prison muster fluctuates daily due to arrests, court decisions and releases but has been sitting around 10,000 over the past few months.

Improve Māori outcomes

A key priority for the Government was tackling the over-representation of Māori in prisons and it has made good progress on starting this, committing money and resources.

That included a $98m investment from the "Wellbeing Budget". It announced a whānau-centred pathway to tackle Māori reoffending rates. It has introduced the Hōkai Rangi strategy that will treat the person and not just the crime. The move will see prisoners remain in Māori units all through their sentence, instead of the current 13 weeks. Topia Rameka was also appointed as a dedicated Māori deputy chief executive.

Facilities

The Government wanted to work towards decommissioning double-bunking, a practice to deal with overcrowding but one that was widely criticised by human rights groups. However, due to a legal loophole, double-bunking will continue for some time yet.

Although it chose not to build a mega-prison at Waikeria, as planned by the previous government, it is building a 500-bed facility alongside a 100-bed mental health unit there.

Education

Labour has had more success fulfilling its education promises than in areas like housing and health, although its wins have not been uniform across the board.

Education Minister Chris Hipkins clearly likes to centralise things. He is moving ahead with his huge programme to roll all the polytechs and institutes of technology into one gigantic institution, against considerable lobbying.

Hipkins also commissioned a massive review of the Tomorrow's Schools framework which has set out how schools have been governed since the late 1980s. He is yet to respond to the findings of that review – which recommends sweeping changes to make schools far less competitive and less reliant on their boards of trustees.

He's also ended the charter school experiment pushed by ACT – a big win for the teacher unions – and negotiated his way through the teachers' "mega-strike", eventually finding $1.4b extra money for them, and restoring pay parity between primary and secondary school teachers.

In tertiary education the Government moved quickly to establish its "fees-free" policy for first academic students, so students in the 2018 academic year could take advantage of it. Students at university can access it for their first year while those in apprenticeships can access it for their first two. The scheme has not significantly lifted enrolment numbers, which has ended up making it cheaper than the Government expected, and led to some criticism.

Hipkins has argued that the Government is a victim of its own success here, as the tight labour market means it is much easier for young people to get jobs and opt not to study. Either way, there are thousands of kids with less student debt than would otherwise be the case.

The minister also moved fast to boost the student loan living costs and student allowance (that doesn't have to be paid back) by $50 per week, as promised. But a commitment to restore the post-graduate student allowance is missing, presumed dead.

It is not the only promise in trouble. The pledge to end school donations by offering schools $150 per student if they promised not to ask for donations has been shrunken to only cover decile 1-8 schools, and has only been taken up by about a third of the schools eligible.

Welfare Reform

An overhaul of the welfare system was a key promise of the Labour-Green agreement. Two years on and true transformation awaits. But a suite of payments and tax credits have boosted the incomes of 385,000 low-income families by, on average, $75 a week.

The Government commissioned a report by the Welfare Expert Advisory Group and received 42 recommendations in April, including increasing main benefits by up to 47 per cent, reforming Working for Family tax credits, and investigating rent-to-buy housing schemes.

Social Development Minister Carmel Sepuloni has accepted three recommendations so far. A sanction on solo mothers has been removed, and the amount beneficiaries can earn before their benefit is cut has been increased.

Critics of the welfare system say the Government has only made a first step, and are demanding the $7.5b Budget surplus be spent.

The numbers receiving welfare have expanded. In the past year, more are receiving a benefit, hundreds of thousands more are receiving hardship grants, and twice as many are receiving housing grants.

Work and Income staff have been instructed to make sure people are receiving all available entitlements, and more than 250 case managers will be hired in four years. The Government says reduced barriers mean thousands are receiving welfare they need. It says this is why, despite unemployment being very low, beneficiary numbers have risen.

Ardern said on Monday, "there are some barriers that have been removed by Work and Income, and I've been told that is making a difference".

Many say the Government has made a first step, tampering with hardship at the margins as housing prices continue to drag families under.

More people on Ministry of Social Development (MSD) books can, in part, be attributed to a change in Work and Income offices. Sepuloni has hired 263 "employment focused" case managers, and instructed staff to ensure people get the full entitlements available.